For the past week, my daily routine has been abnormal. Instead of hearing my alarm in the morning and instantly getting up to get ready before I must leave to drive into work, I have been turning the alarm off and going back to sleep for a while in the hopes that it will help my body heal from what plagues it. Instead of spending eight hours at a desk working on orders, I find myself spending a lot of my day idling aimlessly around my house, trying to find ways to kill time without any energy to really devote to anything.

And even once my illness recedes, my patterns will still be off-kilter in other ways. I may begin to get up with my alarm and rush to get to work, but things will be different in every other aspect. I’ll have less traffic impeding me on my way into the office, since many other people are in quarantine and kids aren’t in school. I’ll have to devote more time and energy into procuring my weekly supplies (groceries), as every store in my area has been completely wiped out, and will likely have a restricted selection for weeks to come. And I’ll have to be more considerate about keeping enough energy to cook, since I won’t be able to rely on restaurants and fast food to help me out on days when my brain or body needs an easy meal.

We are living in strange times, you and I. In the wake of a global pandemic, many things have changed overnight for most of us.

As I ponder how surreal everything feels, I find myself frequently thinking about the intercalary days, and how their existence is unique in every aspect. For those of you who don’t know what the intercalary or epagomenal days are, they are the five days that precede Wep Ronpet. These days are said to have come about when Re wouldn’t allow Nut to birth her children on any day of the year. In order to help solve Nut’s problem, Thoth decided to bet on a game of Senut with Khonsu, and upon winning, Nut was able to give birth on these five days that existed outside of the year.

When I think about how we are living right now, I can’t help but feel like we’re living in a prolonged version of the intercalary days. That we are living in a time outside of time. What does it mean to live in a time outside of time? To get a better idea, I decided to take a look at how the intercalary days were viewed in antiquity. There isn’t a lot of specific information on the intercalary days, but the information that I had feels applicable to what we’re dealing with now.

The intercalary days are said to exist outside of the year, and that makes them peculiar. While many modern Kemetics don’t seem to attribute any sort of eeriness to these days, in antiquity, they were often seen as a time of trepidation. I suspect that this has both a mythological and a more “mundane” component to it. From a mythological perspective, Nut was ready to give birth, but couldn’t until these days were created specifically for her and her needs. Child birth is inherently dangerous, especially before the modern era. It stands to reason that both the aspect of “this is a limited window of time to do something that another being doesn’t want me to do” and “this is childbirth and that is risky to my health” could have played a role in interpreting these days as being inherently apprehensive.

But there is also the mundane aspect of where these days fall within the seasons of ancient Egypt. Situated at the end of the dry season, these days were often fraught with some amount of unease. The dry season was often a time of rationing and careful planning of resources. Since nothing substantial could be grown during this period, and there was limited amounts of water as the riverbed becomes dryer and dryer under the summer heat, the Egyptians knew that they needed to be careful how they utilized their resources until the inundation came. So as the dry season inches onward through the summer, resources become more and more scarce, and with that, an increase in concerns about the future. Will the inundation come? Will we have enough to survive until we can plant more food? Will we get through the summer without illness?

There is also the simple fact that these days manage to exist outside of the year somehow. That ultimately makes them a liminal time and space, a threshold between the old and the new.

To me, where many of us are living now fits very well with the views of the intercalary days from antiquity. Things are abnormal. Our patterns are broken or augmented in ways we’re not used to. Things are not reliably available to many of us, and there is no guarantee that things will be reliably available to many of us anytime soon. There are fears of illness, hunger, and a lack of resources. There is a lot of trepidation in the air. We are stuck between how things were, and an unclear future that has yet to fully manifest.

And that is the most important thing to keep in mind as we navigate through this set of prolonged intercalary days: they may be fraught with danger, but they are also ripe for inducing unforeseen change (both good and bad). There is a lot of instability with our system right now. This is scary and terrifying, but it is also the best time possible to incur long-lasting change that gives people more resources to live and thrive once everything is said and done. Liminal times and spaces don’t follow the rules of what is expected. They are the edges that exist where two systems or spaces meet, and these spaces are known for their intense biodiversity and bending of the rules.

You can see this in the original myth that defined the intercalary days, too. Re didn’t want Nut to give birth because he knew that her children would invoke a regime change. It would incur a new way of life for all of the NTRW, and he didn’t want to see that happen. Every year, the intercalary days are meant to be an intense time of chaos before everything resets and ma’at is restored anew during Wep Ronpet.

These liminal spaces are meant for change and transformation. This liminal space will likely be no different, but the question becomes: what sort of change will we fight for?

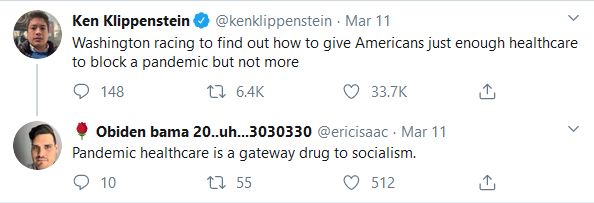

For the first time in a long time, retail and food workers (among others) have the means to potentially leverage their position to gain workers rights and benefits that were due to them forever ago. There are people trying to push state governments to utilize vacant housing to give the homeless shelter during these challenging times. There is an entirely new wave of people talking about classism and how class intersects with politics and daily living in new places that I haven’t seen in the past. There are people who are starting to see that if there is a time to start pushing for hard-hitting change, this is it.

On nearly every video or post that I’ve read regarding COVID, it seems like the conclusion always ends up with some sort of “if we all band together, things will be okay!” and I don’t want that to be the case with my post because its simply not true. There are people who will not survive this. There are people whose lives will be irreversibly changed by this. This situations is bad, and this is merely a post about the potential tiny silver lining of a really bad situation. Many people have had their entire life thrown into turmoil because of this, and I certainly don’t want to make it sound like their suffering is “worth it” if it means potential change, because that’s not the case.

Instead what I am trying to suggest is that perhaps the means to insure that this sort of thing doesn’t happen again is within our grasp, and if it is, we should do what we can to make that happen. Because while the intercalary days are a mere five days of uncanny discomfort, we are more likely to be stuck in this liminal space for months, if not a full year and some change (vaccines aren’t expected to be ready for about 18 months, which is when pandemics usually recede.) Things will be unsteady for a while yet, and our best chance of survival will come from mutual aid that we give one another during these difficult times.

I think it is imperative that we look at the conversations being had, and consider what we could be doing during this time in relation to the changes going on around us. To look for those ripples of change, and to see if there are other things we could put our backing into that would help other fellow humans have an easier time of it on this rock — both within this liminal time, and beyond it. It is the responsibility of all of us to help maintain and foster ma’at, and from what I can tell — there are a whole lot of opportunities being made for increasing ma’at right now even in the face of overwhelming isfet.

And I think we should do everything in our power to seize those opportunities and create a world we want to live in.